Chungking Express

I recently had the opportunity to see a re-screening of Wong Kar-Wai’s 1994 crime-drama-comedy film, Chungking Express, in the theater. I was struck by how impactful this film was the second time around, having first seen it on the TV at home. There were multiple details and nuances that I didn’t pick up on the initial screening, and I think seeing it within a different context of my own life gave it a different impact as well.

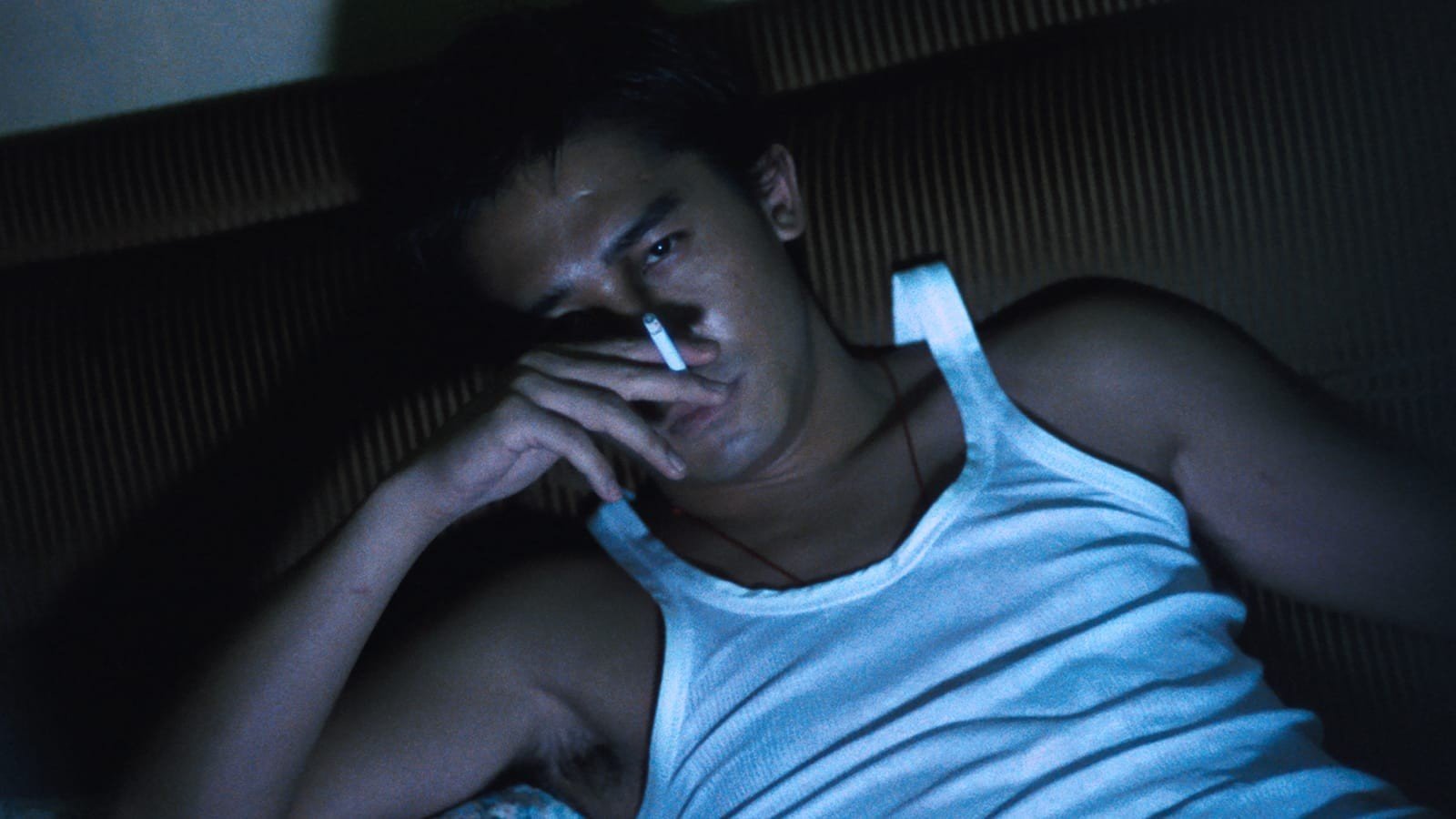

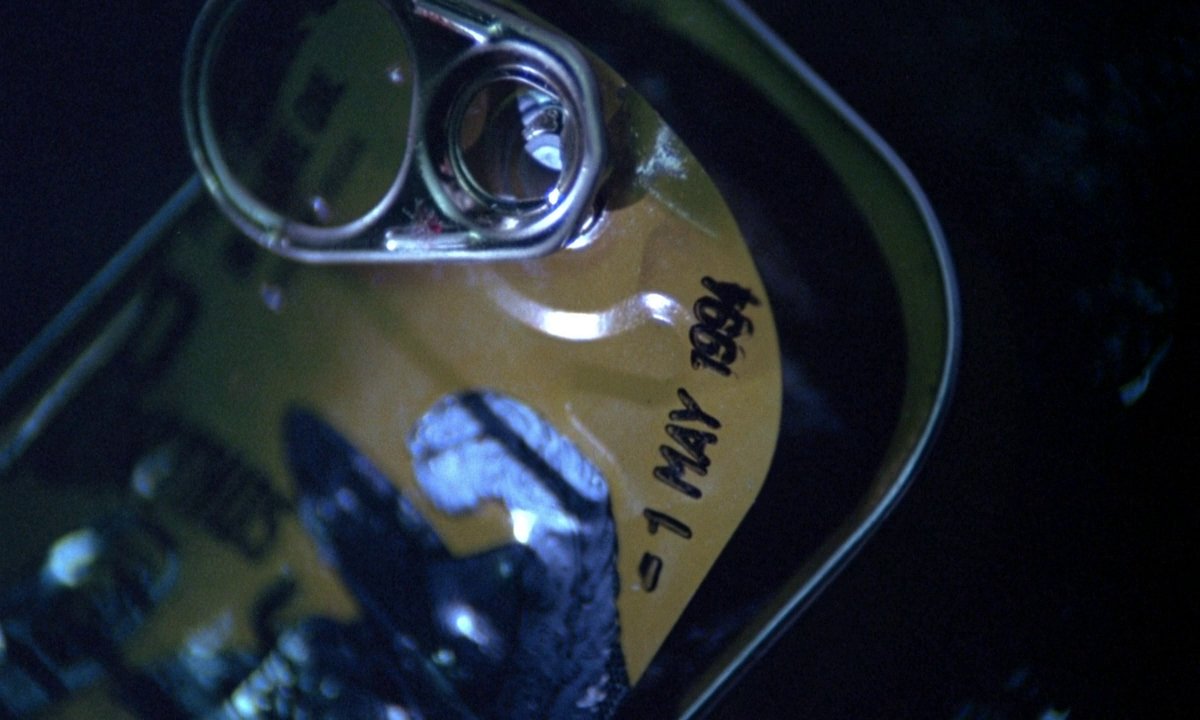

The film is split into two shorter vignettes that follow two lonely and lovestruck beat cops in 1990s Hong Kong. The first of the short stories is somewhat more accessible than the second – a young, handsome police officer, referred to as ‘Cop 223’ seems to be pulled straight out of a romance flick. He’s just had his heart broken by an ex-girlfriend and has developed a serious obsession with expired cans of sliced pineapple. After gulping down nearly 30 tins of the stuff, he’s feeling a bit queasy and decides to head to the bar, justifying over narration that alcohol will settle his stomach. After becoming sufficiently inebriated, he promises himself that he’ll fall in love with the first woman who walks in the door, who happens to be a femme-fatale drug trafficker that he ran into earlier that day while chasing a wanted man through a crowded market. The cop makes a stumbling attempt to win the woman over. She continues to show little interest in him and even assures him that she won’t like him because he’s too young. Even though they technically end up “sleeping together” that night, it’s not in the way you’d expect. It’s enjoyable to see a heartbroken man get denied what he thought he wanted yet still manage to find satisfaction in the outcome.

The transition from the first half of the story into the second is a genius one that works seamlessly – using the ‘Midnight Express’ café that many of the film’s scenes are shot from as a grounding point. Right before the shop owner succeeds in upselling Cop 663 on some fish and chips for a flight stewardess-turned-ex-girlfriend-to-be, the other Cop bumps into a brash, short-haired young woman – noting that “[It’s] the closest we ever got. Just 0.01cm between us. I knew nothing about her. Six hours later, she fell in love with another man”. This ‘other man’ happens to be Cop 663 – classic voyeurism.

Being lonely in an urban environment, passing by thousands of people daily, all with different lives, each presenting an opportunity to connect – it hits hard. Every light glowing through every window in every apartment tower has a story behind it. Cop 223 makes note of this over narration in the very first lines of dialogue “You brush past so many people every day. Some you may never know anything about, but others might become your friend.”

Narration or voiceover is often used as a crutch to help explain or speed through crucial plot points. However, the narrations in Chungking Express are the exact opposite of that – they read like beautiful, intimate, and inspiring journal entries that add incredible depth to each character. This gives them a life beyond the film and provides some comedic relief, which is perfectly peppered throughout both storylines. Cop 223 sarcastically narrates that “We're all unlucky in love sometimes. When I am, I go jogging. The body loses water when you jog, so you have none left for tears.” His way of dealing with a broken heart is making light of it – as long as he’s not busy searching for cans of expired pineapple.

There’s a constant personification of inanimate objects that manages to be funny while simultaneously exposing a feeling of loneliness and desperation. These cops long to connect with someone, or something – even if it’s a mere bar of soap. It makes you question - maybe these guys could’ve been friends? Cop 223’s request to purchase expired pineapple cans when there’s none left in the store is downright hilarious – “You realize what goes into a can of pineapple? The fruit must be grown, harvested, sliced, and you just throw it away! How do you think the can feels about that?” Yes, it’s a ridiculous proposition, but if we look deeper, it’s really a vehicle for him to express and project his own internal struggles when he feels nothing in his life is working. He’s put time and effort into his relationship with May, yet just because an expiration date has come, he's expected to let it go and move on. How can this world expect him to handily dispose of something in which he’s so emotionally invested? And don’t we obsess over time in our own lives in our own, unique ways?

In another scene, Cop 663 roams through his apartment, inattentive of objects re-arranged by the enigmatic Faye, he directs rhetorical questions to a wet towel – “It was such a relief when I saw it crying. It may look different, but it's still true to itself. It's still an emotionally charged towel”. Cop 663 is rather stoic throughout the film – he rarely shows emotion himself, but his dialogue with random objects gives subtle hints to the turmoil that lies deep inside his soul. Charles Bukowski once said that “Poetry is what happens when nothing else can.” Maybe he’s reached that point, and his last resort is to vicariously experience the world through anthropomorphism. Is he so numb that he can’t cry anymore, and can only feel it through a towel dripping on a windowsill? He knows Faye has been sneaking into his apartment, having caught her in the act multiple times - but we rarely see him question her or her motivations. He’s so apathetic that he just accepts it the way it is.

Quention Tarantino, who adores this film, noted that his own aesthetic is “…based not on the novel, but on the poetry between the lines.” That’s the gray area in which Chugnking Express operates. Its most touching moments aren’t explicitly said, shown, or explained, but rather suggested and inferred. They aren’t spoon-fed to the viewer - the director and writers respect you enough to figure that out on your own and form your own opinions about it.

The soundtrack is all killer, with no filler - there are only six songs used throughout its 90-minute runtime. Though the songs are used as motifs, they aren’t repetitive. Instead, they hit with a new emotional impact every time you hear them because the surrounding context has progressed, making them rather iconic. The fact that much of the music is also diegetic - that is, the characters are presumed to be hearing it as we do - only adds to the immersion in the film. Any time I hear “California Dreamin’” by the Mamas and Papas, I can’t help but think of Chungking Express. I also found myself rushing to listen to Faye Wong’s beautiful and forlorn cover of “Dreams” again and again – it rivals the original record by the Cranberries.

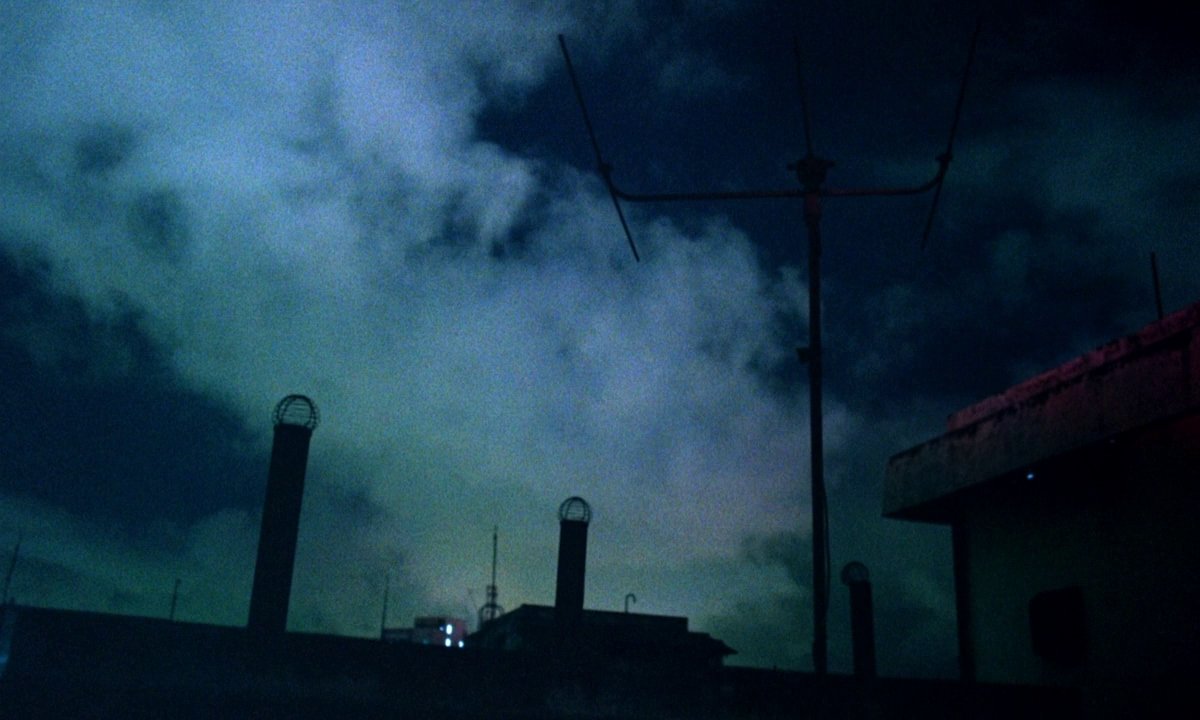

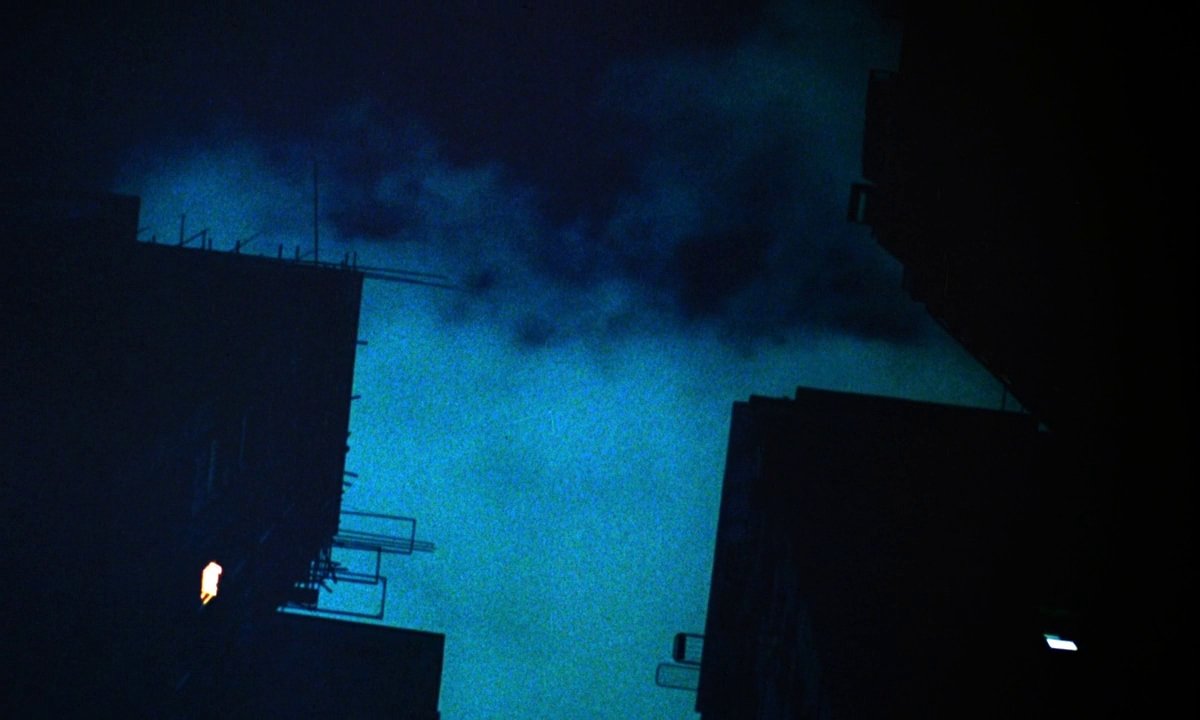

The cinematography in this film is one-of-a-kind. I could spend this entire review geeking out over the gorgeous AGFA Film Stock it appears to be shot on, or the clever use of handheld documentary-style shooting used in low-FPS chase scenes. The first half of Chungking Express is a nocturnal, brooding film. It’s slathered in mood and drenched in every noir archetype you can think of. If it was condensed into a single painting, it’d be Vincent Van Gogh’s impressionist masterpiece, Starry Night. If it were a music album, it’d be “Heaven or Las Vegas” by the Cocteau Twins. In contrast, the second half is brighter and more dreamlike. The sun is out, and many of the scenes are shot in the daytime – especially the apartment sequences. This lightens the mood but still manages to remain cohesive with the overarching style and mood. Christopher Doyle did an amazing job.

The location choices are appropriately minimal. Most of the scenes take place in the cop’s apartments, the midnight express cafe, or in Hong Kong’s compressed maze of businesses, hotels, and restaurants. I later learned the real-world location is the present-day Chungking Mansions of Kowloon, which bears a striking similarity to the former Kowloon Walled City. The building complex still stands on Nathan St. If you’re interested in this type of compact urban development, I highly recommended checking out Greg Girard’s “City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City”.

Chungking Express opens with a unique blend of neo-noir and 90’s drama-romance, which is a compelling way to introduce a film that segues into an experimental art-house fever dream sequence. It gives the viewer some brain food to nibble on, then ventures into uncharted territory once you’re hooked. And that’s how I felt watching this film – it hooks you and refuses to let go.

The central theme that ties everything together is the obsession with time passing. It’s repeated constantly throughout – the camera lingers on shots of the Twemco Flip Clock and zooms in on expiry dates embossed into metal tins. The characters obsess over it - 223 remembers the exact time he was born and makes a point to tell us he hasn’t technically turned 25 yet.

I could go on into the more subtle micro-themes, like timing not being correct for romance (super cliche), departures, destinations, and airplanes (typical and obvious), or the doubles - two “Mays”, two flight attendants, and two cops (an interesting but rather unimportant detail). These are themes that have already been explored ad nauseam in countless other films. If there’s one criticism I have, it’s that Chungking Express didn’t go all-in with its experimentalism. If it did, it might be my favorite film of all time. It’s still trying to appeal to an audience in some way.

On a deeper level, Chungking Express is about the bittersweet reality of the human condition. In one of the most poignant quotes from the film, Cop 223 ponders to himself:

“If memories could be canned, would they also have expiry dates? If so, I wish they’d last for 10,000 years.”

Part of being human is wanting to hold on to memories that really mean something to you, even though we know that all memories fade with time. Death is the only constant in a sea of change. We yearn so deeply for something in our lives to be permanent, yet in doing so, we cause ourselves a tremendous amount of emotional anguish.

Exploring this human contradiction is tragic and incredibly powerful because we know how hard it is to admit this and let go. Maybe that’s why we end up doing it anyway. We’re hopeless romantics. What happened to that fleeting, ephemeral memory of a blossoming love you experienced forever ago? Eventually, it all evaporates into the ether. Maybe you find yourself questioning if it ever happened. You begin to wonder if that person ever thinks about you, and if they, too, are holding on to the beautiful memories you once shared together. You want to carve out a little place for them in your heart, but somewhere along the line, you’re forced to accept that place has vanished.

If we can accept that nothing lasts forever, maybe we can begin to re-focus on the importance of living in the moment. Enjoying the present. That’s all there is, was, and ever will be. In the end, I like to believe that Cop 663 has relinquished himself to this truth. While writing him a new boarding pass, Faye asks him:

“Where do you want to go?”

to which he replies,

“Wherever you want to take me.”